The stories of salt are human stories. In literature, religion, and history, when we are talking about salt, we are talking about ourselves; when we look at this substance and its peculiar ways, we see figurations of human qualities. Ideas, crystallizing. The taste of tears. Something so common it’s not worth mentioning. Rubbing salt in wounds or plowing it into the soil. Lot’s wife, looking back at her burning home. And so on.

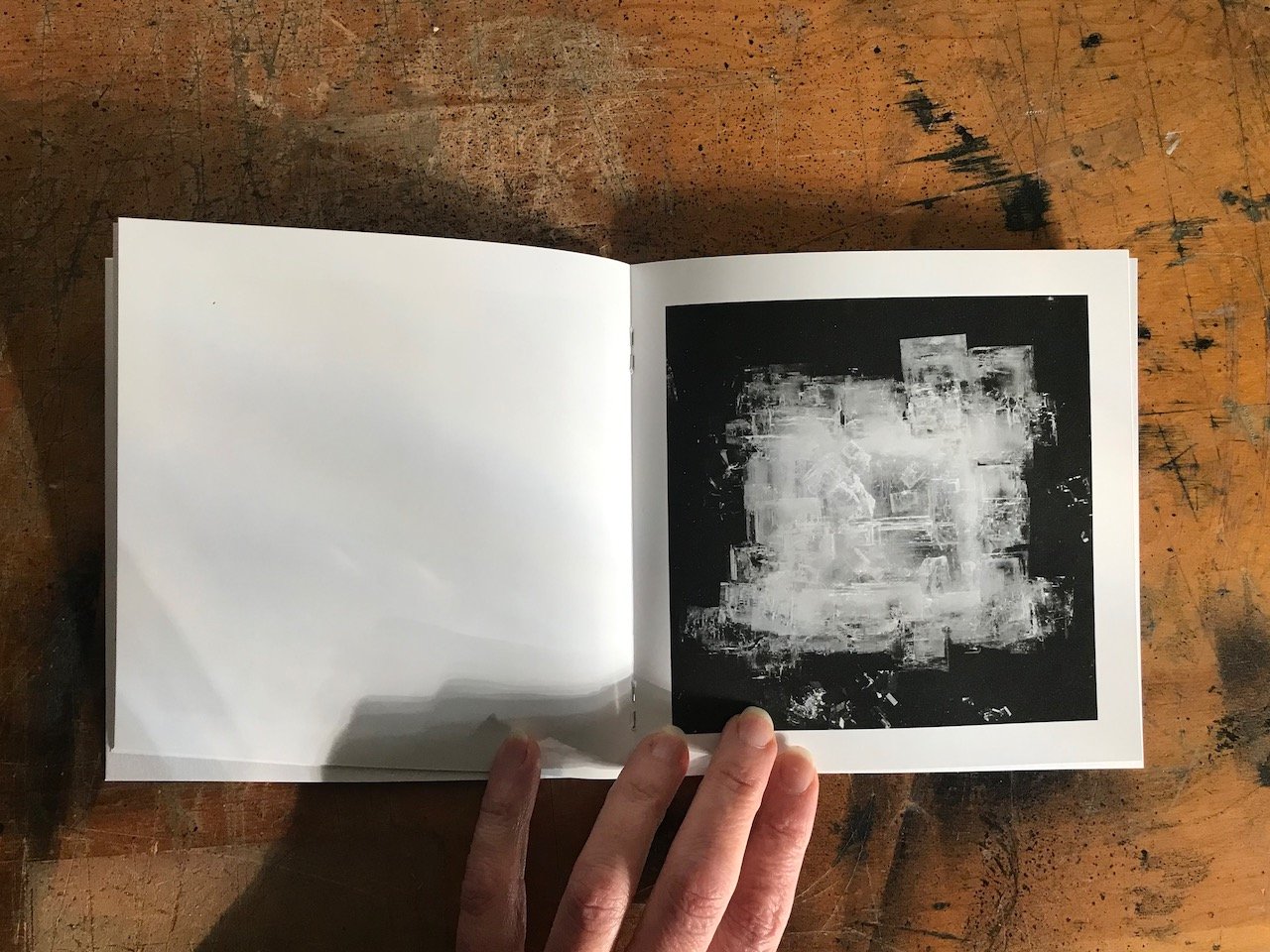

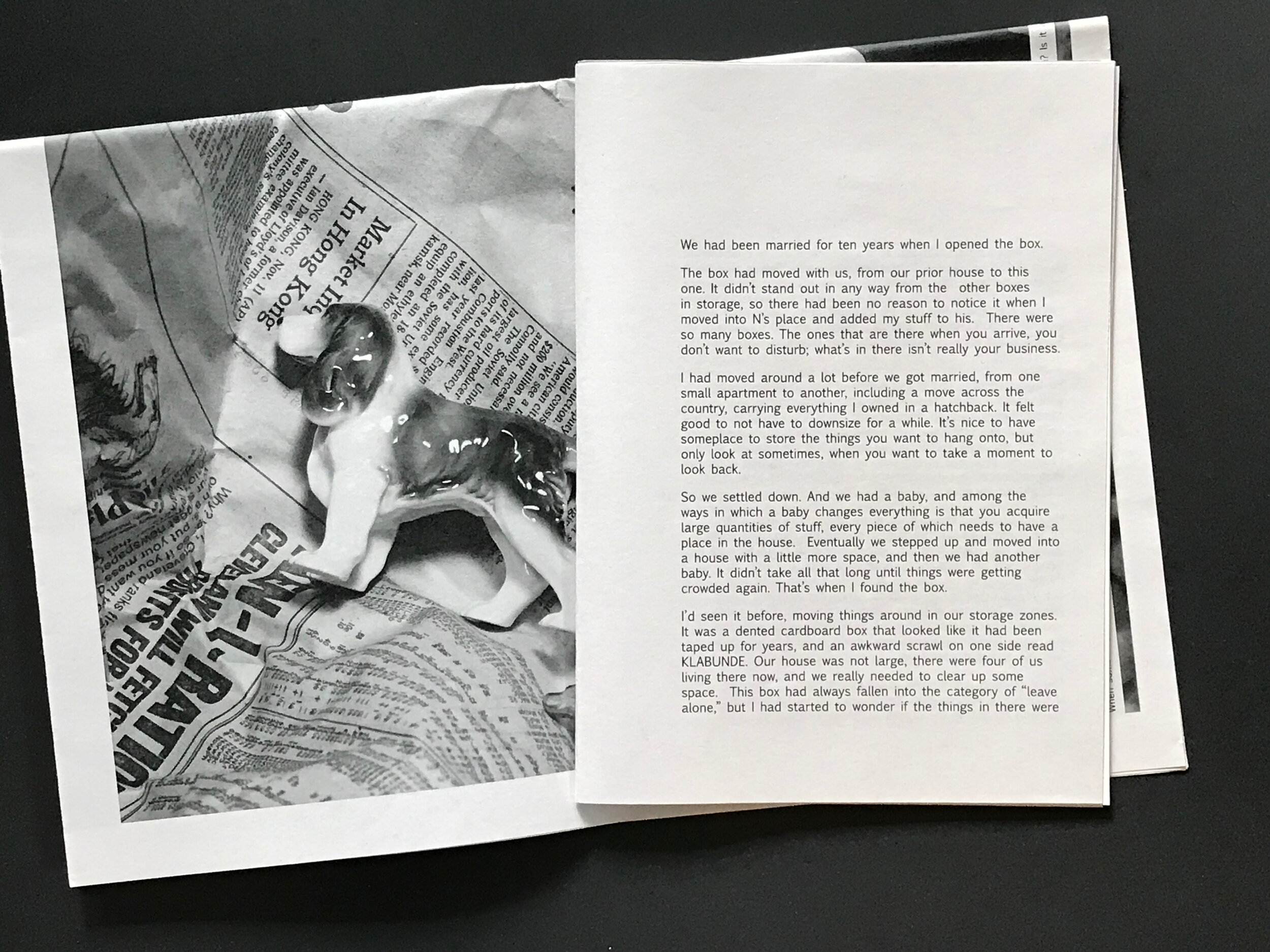

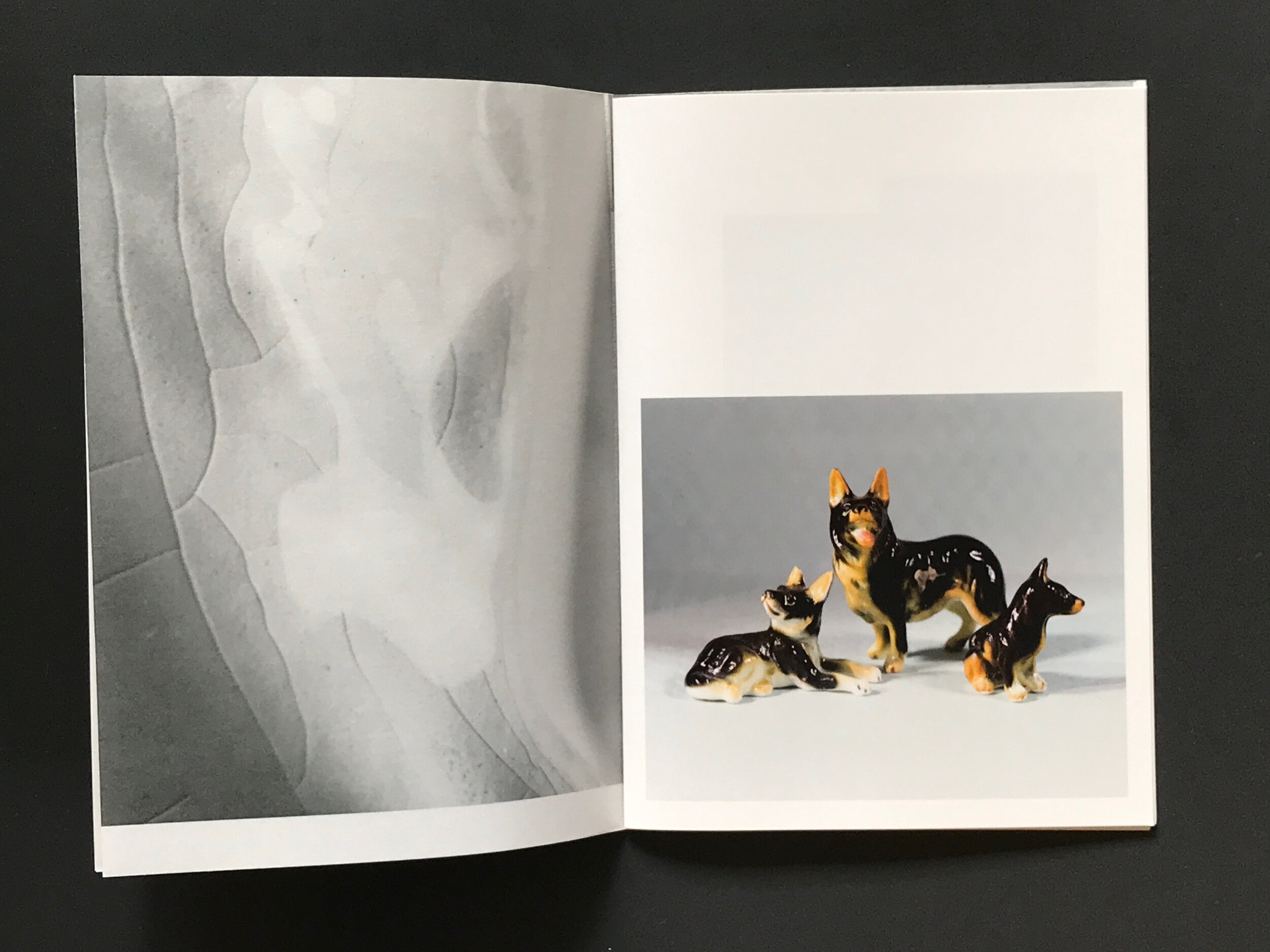

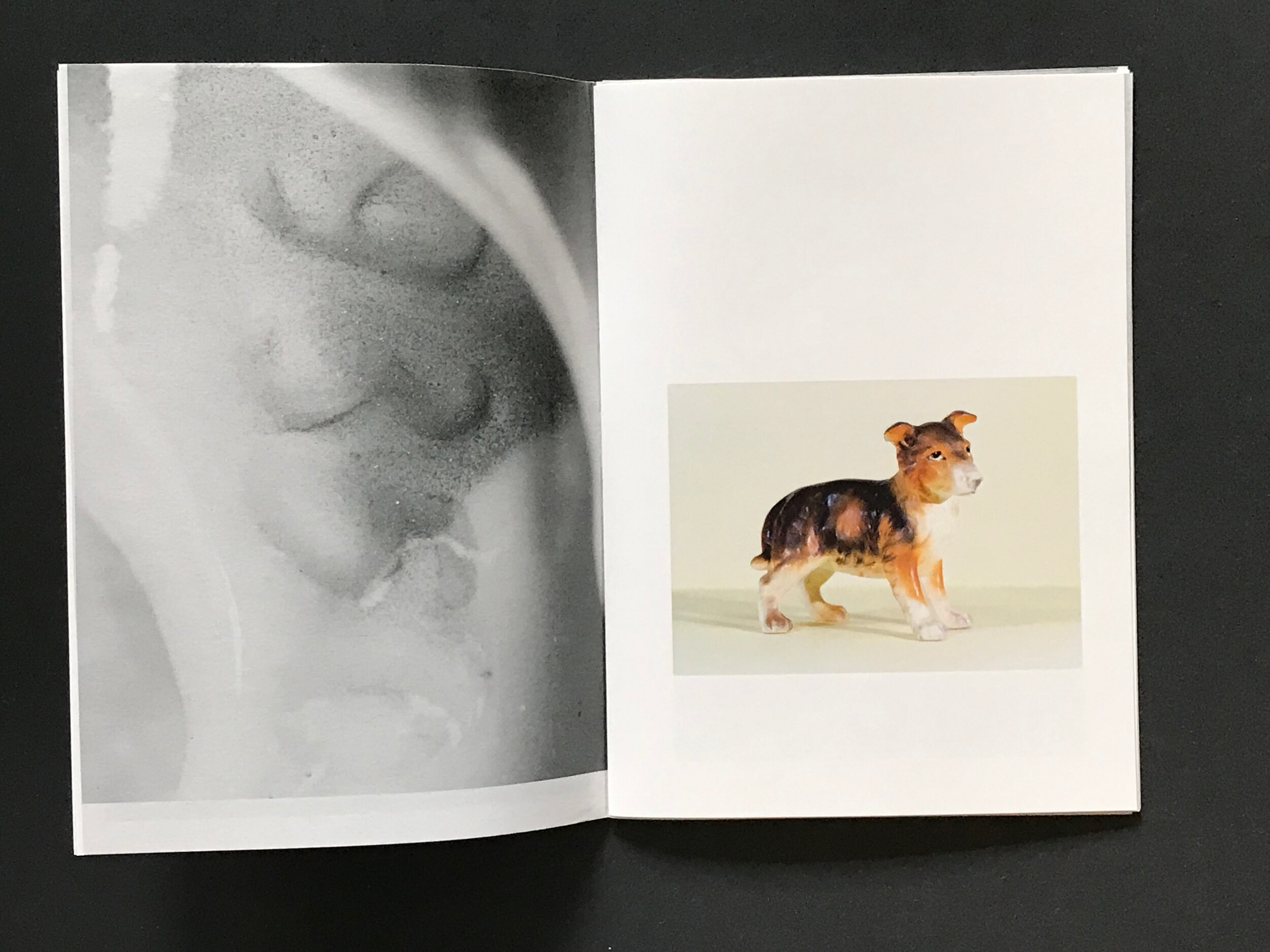

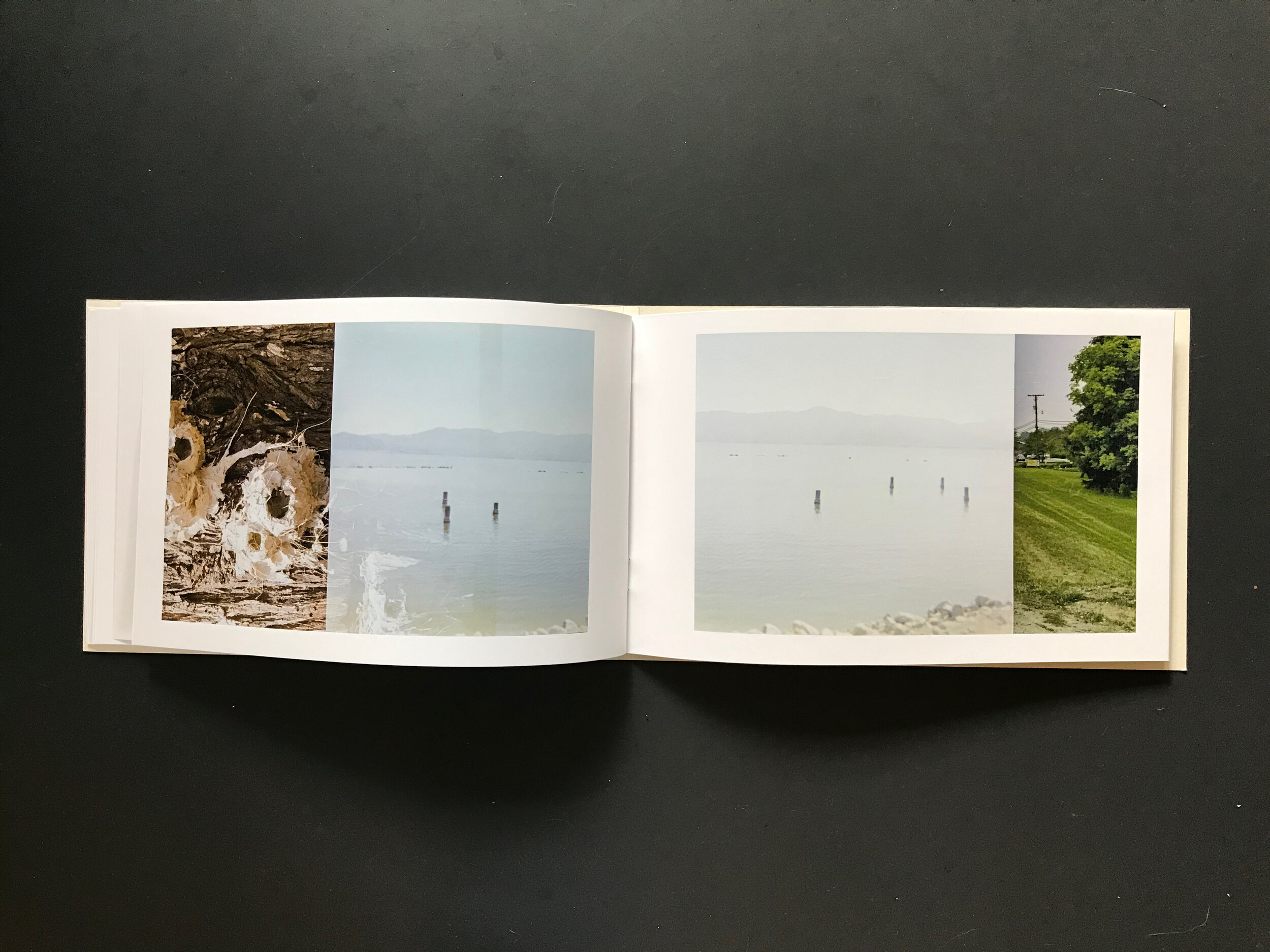

On a material level, the forms that these crystals take are largely dependent on their environmental conditions. I grow these crystals here in an old house, in a climate where temperature and humidity conditions are always fluctuating. Any change creates variations in density, funny shapes and angles, cracks, bubbles, opacity, dustings of tiny crystals that collect on the surface before sinking, countless ways to deviate from clear-edged geometries. These salt crystals take a long time to grow, and any sort of progress can be easily wrecked.

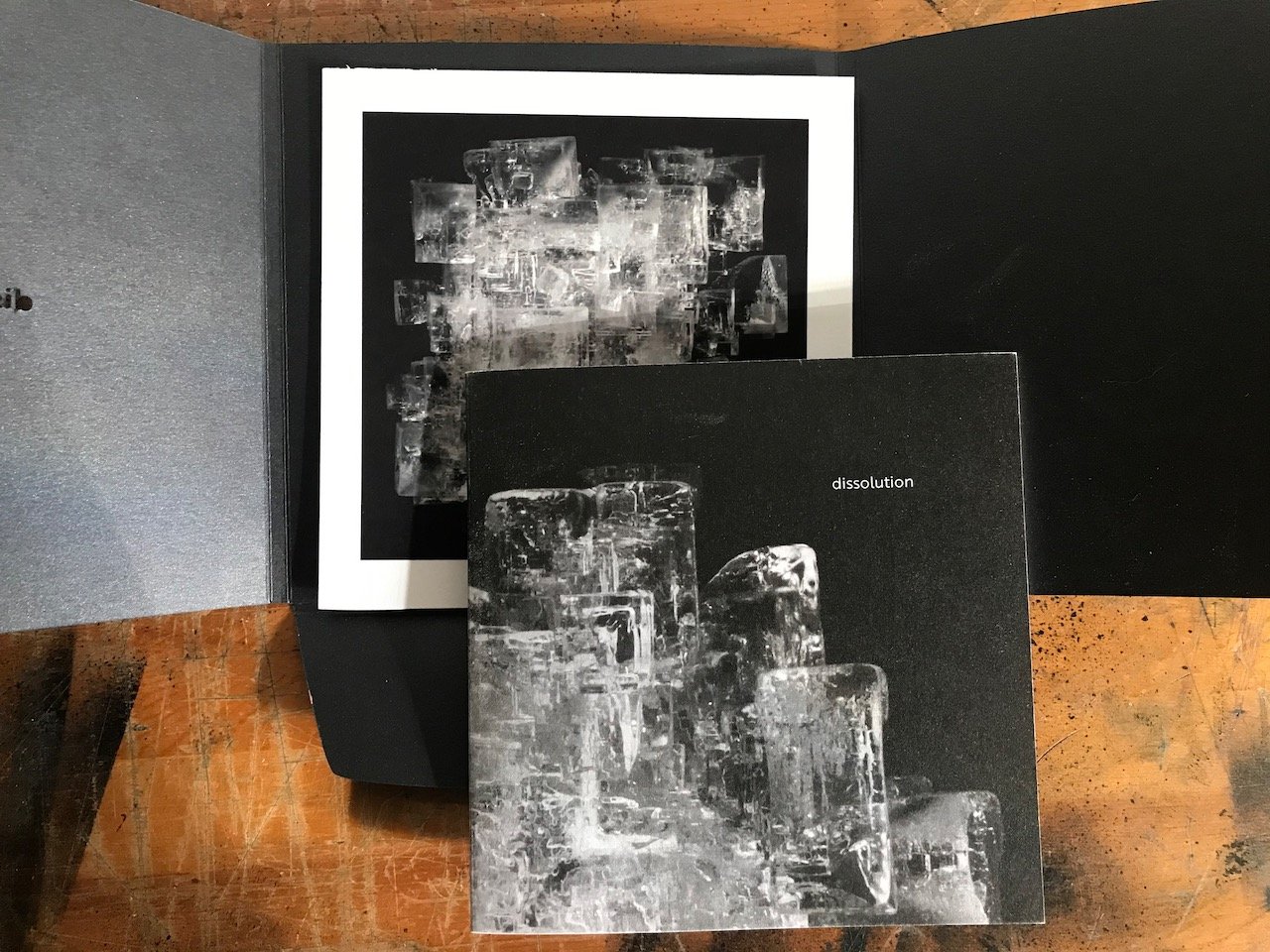

It was the end of 2020. I had a set that had been growing for several months, which had developed some peculiar configurations but were getting interesting to look at. Several had reached a decent size, some of them half an inch across. In preparing to photograph them, I transferred them to a clean dish of saline solution. I quickly realized that the new solution was not fully saturated: the crystals had begun to dissolve. I moved them back to the solution they’d come from, but the process was already underway. I was afraid they were damaged enough that they’d need weeks to build up clean edges like the ones they’d had before, if it were to happen at all (which is never guaranteed). Disappointed, I photographed the best remaining ten of them in a marathon session, and set the images aside. They demanded a lot of focus stacking and were going to take some time to edit, and I prepared to do this on a residency at the beginning of January 2021.

This residency consisted of ten days at Arts Letters and Numbers in rural upstate New York. This was under socially-distanced conditions, which meant working in a farmhouse and cavernous studio with just a few other artists. We shared the spaces amicably and made time for studio visits, but spent most of our days entrenched in solitary work. Each day I’d bundle up to make the trek across the icy street and under towering pines from the house to the studio. The environment was blessedly free of distractions, with no TV and sketchy cell coverage. But there was wifi in the buildings, and I used it to keep in touch.

That was how I found out what was happening in Washington DC on January 6: on my phone, through clips posted to social media. We were respecting one another’s space there, and conversations that day stayed brief and tentative, but as the day unfolded it became clear to all of us that something monumentally terrifying was taking place.

In the studio, I was piecing together a sense of the situation through the twitter feed of writers I followed. Videos took so long to load that I was left mainly with descriptions and reactions. A heavily armed mob had stormed the Capitol in attempt to take over, to do what? Whatever they could; it wasn’t clear; they were chanting about revolution, they were going to halt the confirmation of the election, they wanted to hang the Vice President, they were prepared to kidnap the Speaker of the House, they were hunting down senators, smashing windows, pissing in corridors, trashing offices, beating cops, taking selfies, running off with things they could grab. People were being rushed to undisclosed locations. Bomb threats were announced and never mentioned again. The president-elect was confirmed safe. Eventually the location was secured, the area militarized, a curfew declared.

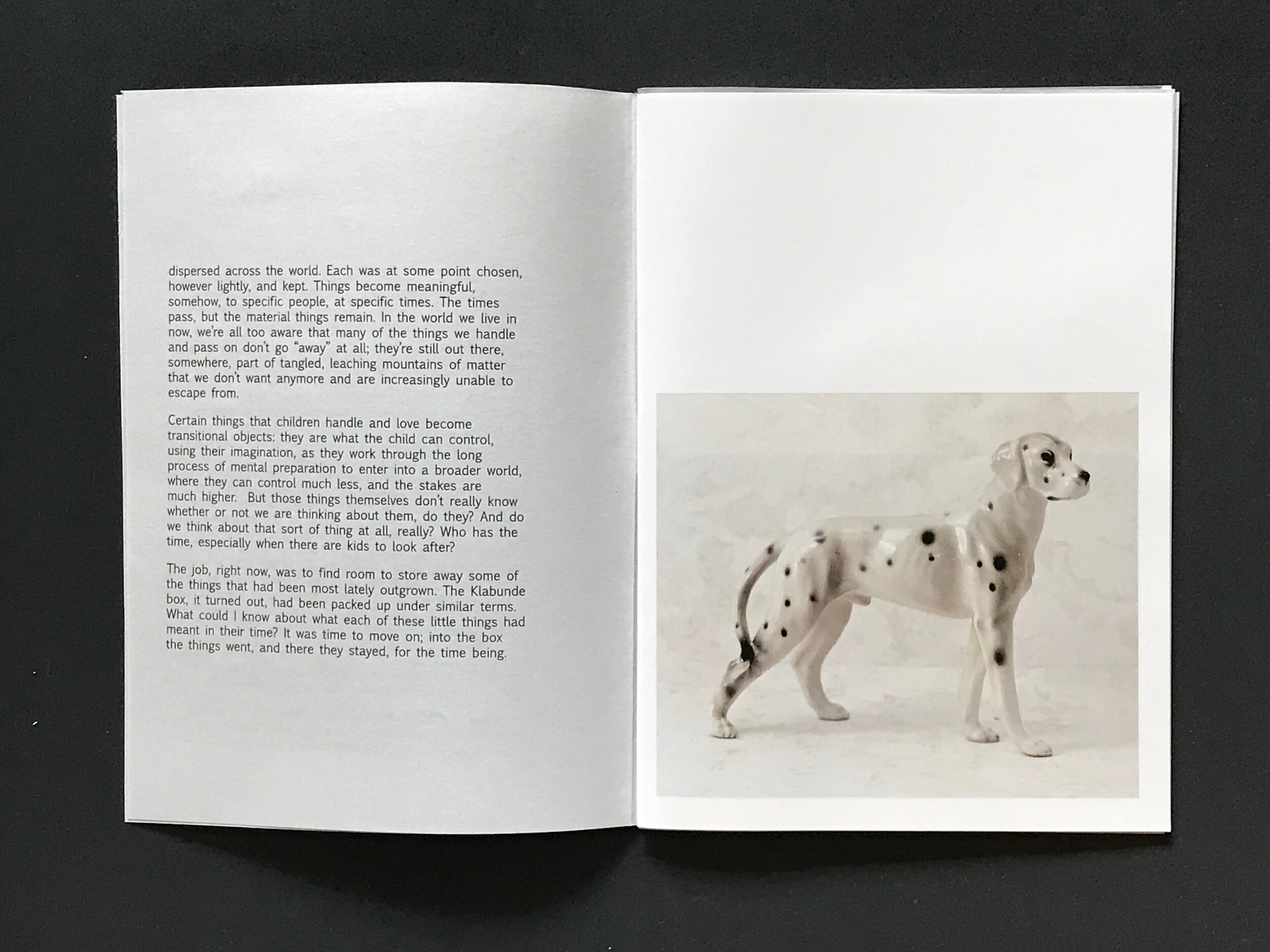

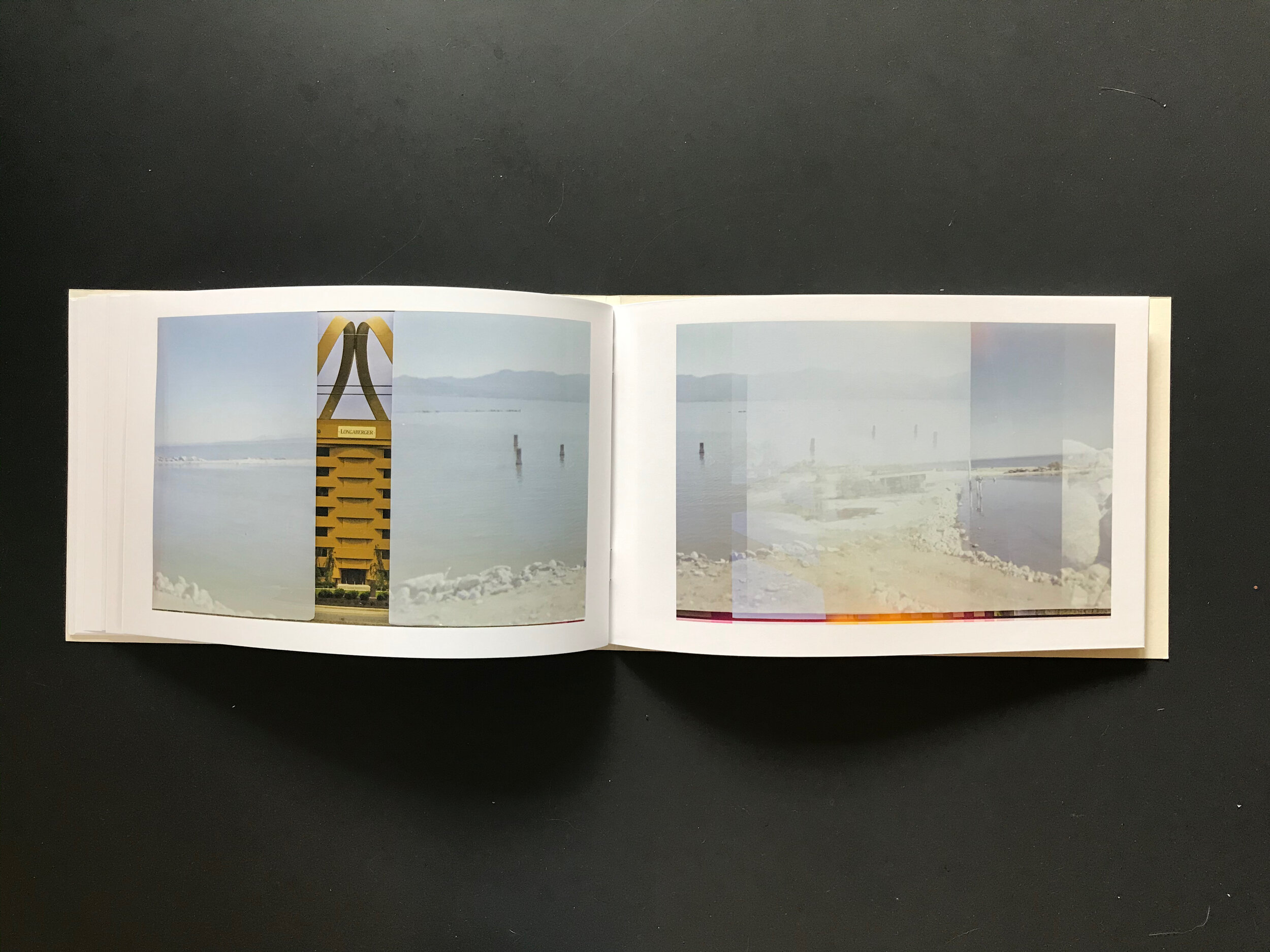

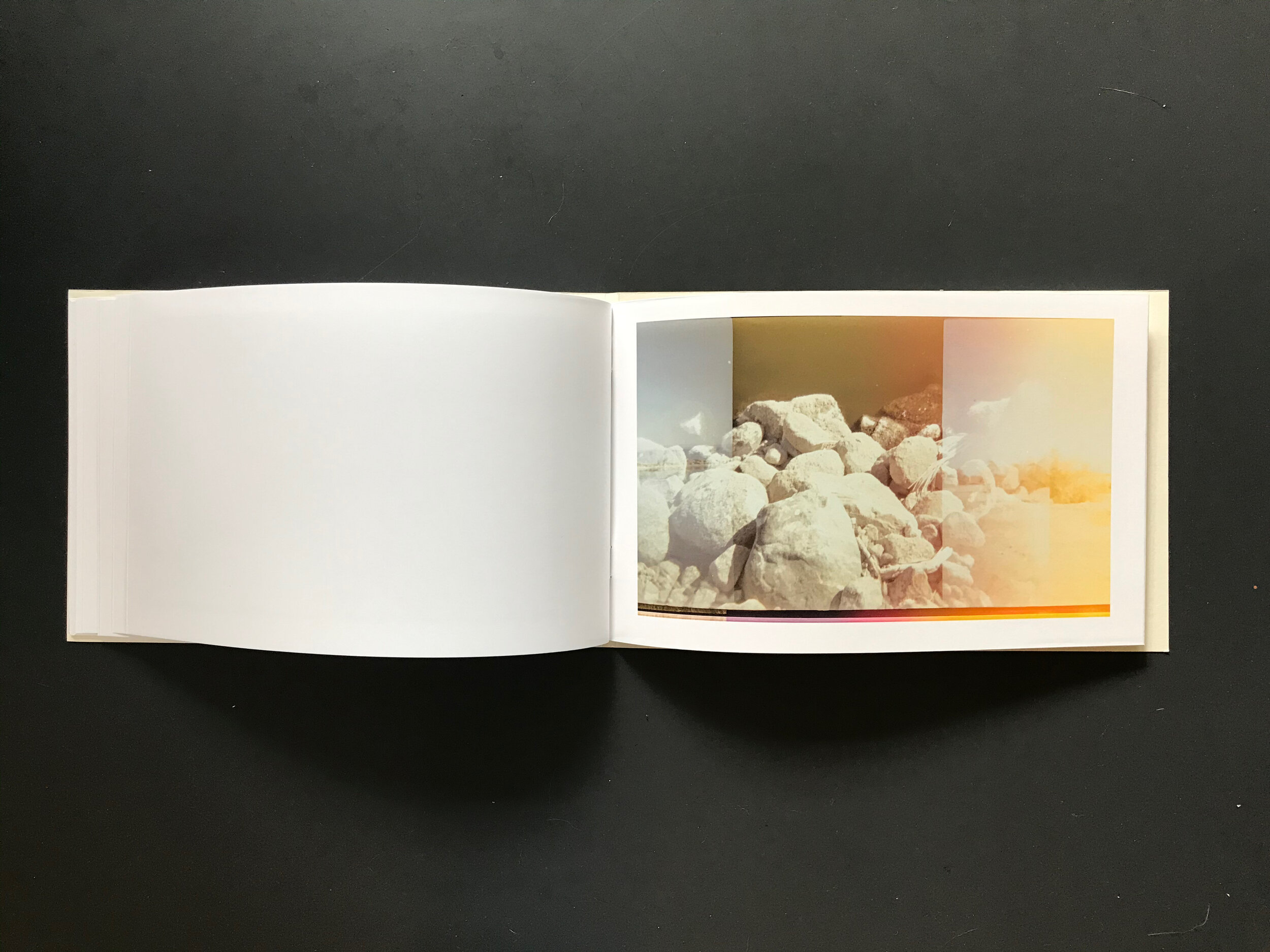

All day I was trying to stop checking my phone for updates, trying to keep working. Work meant piecing together photographs of these weird little mineral configurations in the process of dissolving. Part of the imaginative appeal of salt is the way it constructs itself more or less before our eyes and can dissolve in an instant, only to rebuild again as water evaporates. Geologists speak of the life cycles of rock formations. We all know that salt is a mineral, something from the earth, once underground, or from the sea. It comes to our tables purified and packaged, but it came from somewhere.

Where did this particular salt come from? We’re just consumers, so how would we know? Salt processing and shipping were the economic cornerstone of the Hudson Valley in generations past. A massive share of American salt now comes from mines stretching deep beneath the Great Lakes, some of them a few miles from my Pittsburgh home. Beneath us, salt is rock. How many millions of years did those strata take to coalesce and build? They are dug out with massive amounts of labor and power. They serve their purpose; they dissipate. Over time, those salt strata disperse into the oceans, and somewhere far away, people might collect it with other forms of labor as it crystalizes under the sun. It flows through our system of production and consumption. Humans around the globe are processing salt all day long as we go about our lives. It surfaces on our foreheads when the heat rises, it run down our cheeks sometimes when we don’t know what’s going to happen next. Things that seem solid turn out to have just seemed that way, because that’s where they were in their life cycle. Sometimes we find that we had been taking a certain perspective on the scope of time for granted.

The photographs I was processing on January 6 became Dissolution. The book was completed in March of 2021 and remains available, in an affordable small form with a special edition that includes a hand-trimmed folder and archival inkjet print.