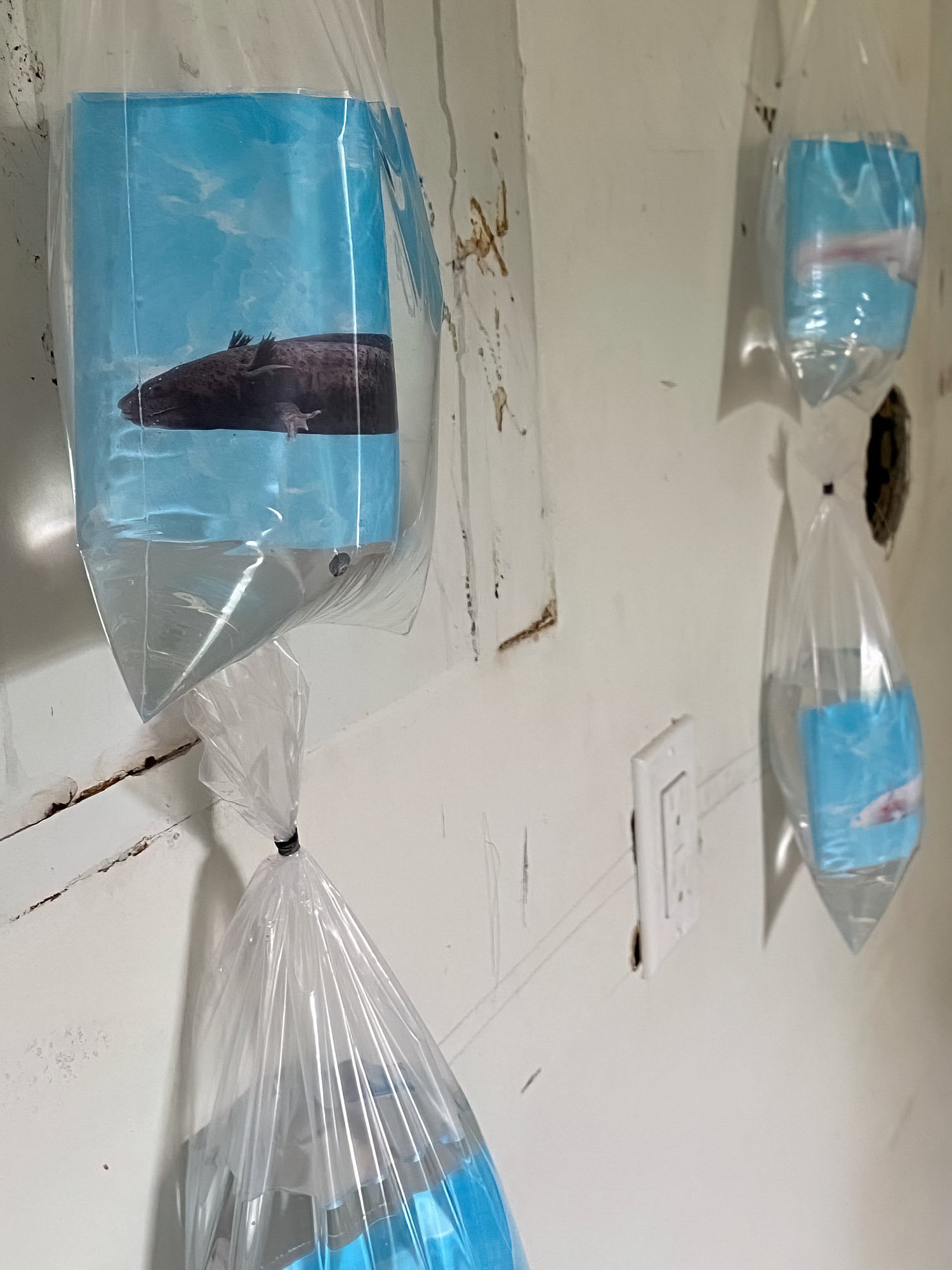

The strata of the earth don’t lie still like the layers of an onion—they move, sometimes steadily, sometimes dramatically. They are moving now. We are walking around on top of the way they have been moving. Lately I’ve been on a deep dive into the geological role of salt. I spent some time exploring a region of Utah they call the Paradox Formation. A few photographs and prints from this work in progress are currently on view at Brew House Arts as a part of And Also Wide: Artist/Mother Lines.

Geologists speak of salt’s plasticity: the salt layers underground shift in shape over time as strata accumulate above them, and under that weight they re-form themselves to push walls and arms up towards the surface. The process has played a substantial role in shaping the spectacular landscape features of Utah. The area is famously home to the Great Salt Lake and the Bonneville Salt Flats—and also to a particular area they call the Paradox Basin. Some aspects of salt’s activity there are visible in the canyons, mesas, arches, and valleys; some have dispersed over the eons, and some remain in massive deposits underneath. As the salt layers reach towards the surface in this region, they carried up with them pockets of space for petroleum, which is drilled in the area today.

The Paradox Valley extends from southeastern Utah into western Colorado. I traveled from Pennsylvania to the Pennsylvanian Paradox Formation so I could roam around in this landscape, shaped by salt over hundreds of millions of years. The canyons and uplifts show the way the salt wall shifted upwards, displacing the strata that had accumulated above, and eventually dissolving. This process created the Paradox Valley, where minerals left behind made it suitable for agriculture. The kind of agriculture that takes place there now, though, is only possible because of massive quantities of water pumped in from the Colorado River. The salt tectonics of the Paradox Basin also cultivated large petroleum deposits, and there are a number of oil fields in the region.

Not far from this area is another salt formation, an immense deposit left by the evaporation of the Sundance Sea, which is mined by the Redmond Mineral Co. They were kind enough to let me join a corporate tour of the source of salt mined for a range of purposes, from culinary to agricultural. And of course they are a popular source in the region for de-icing salt, which facilitates traffic through the mountains all winter. (Petroleum and salt working together again.)

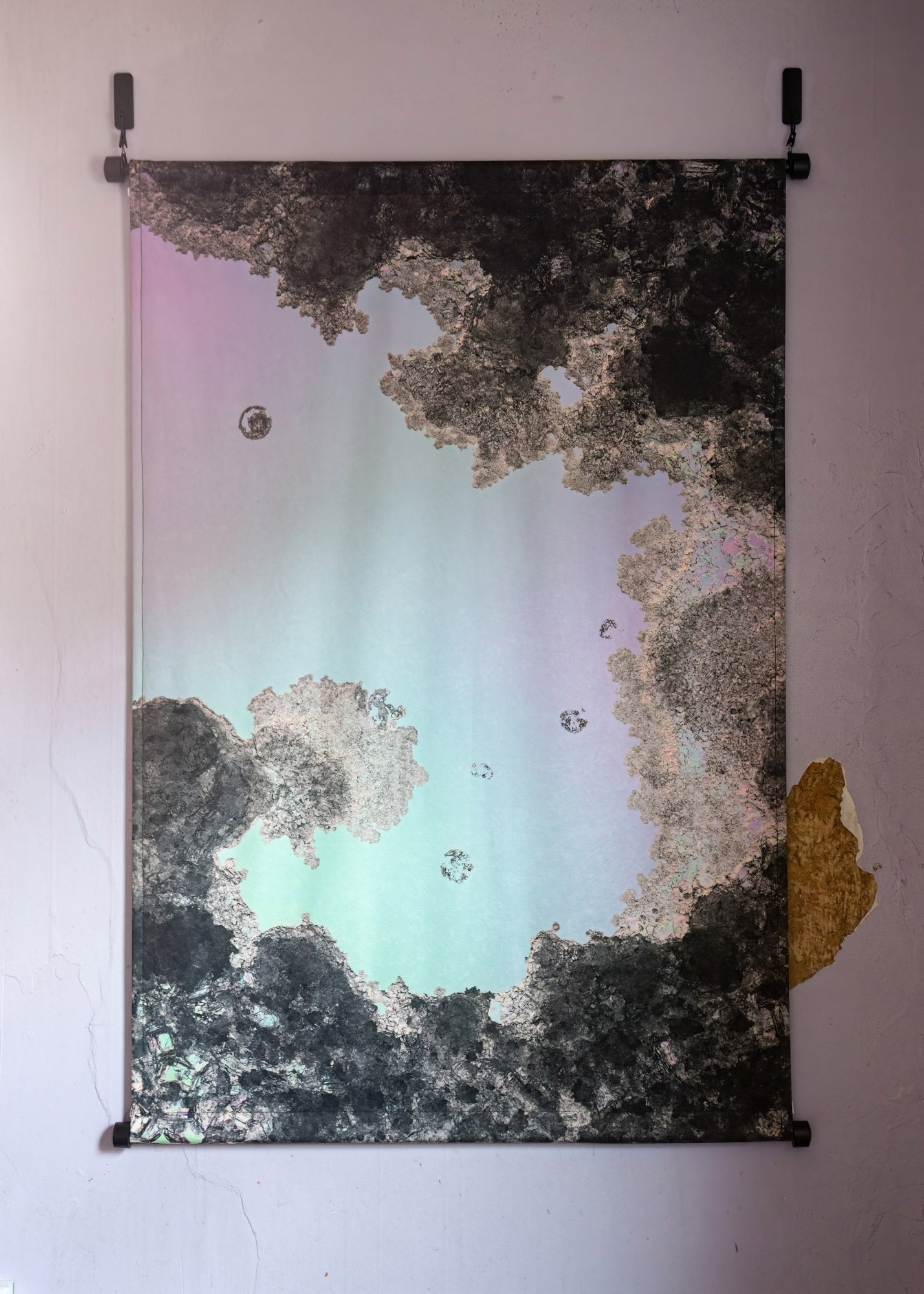

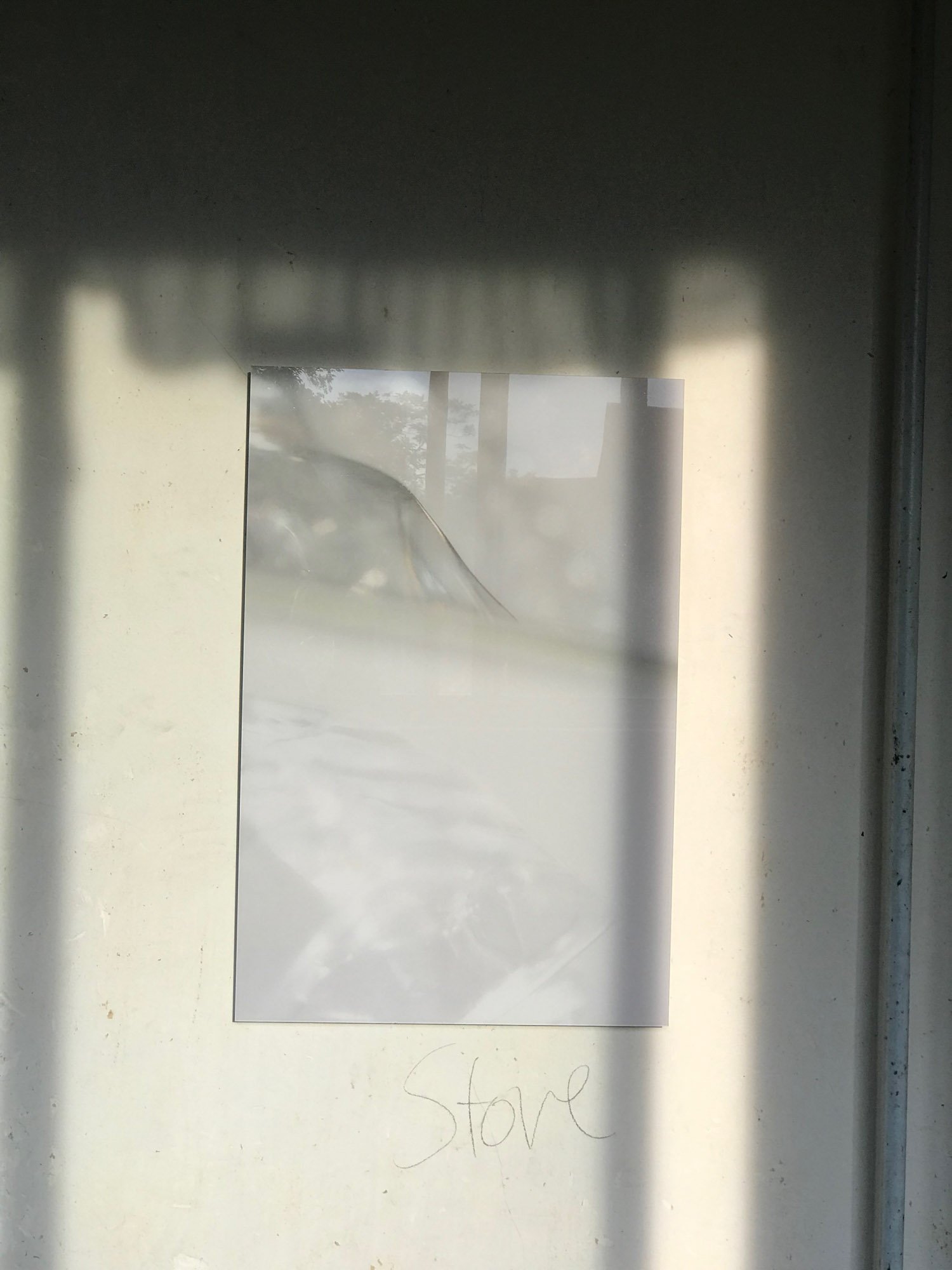

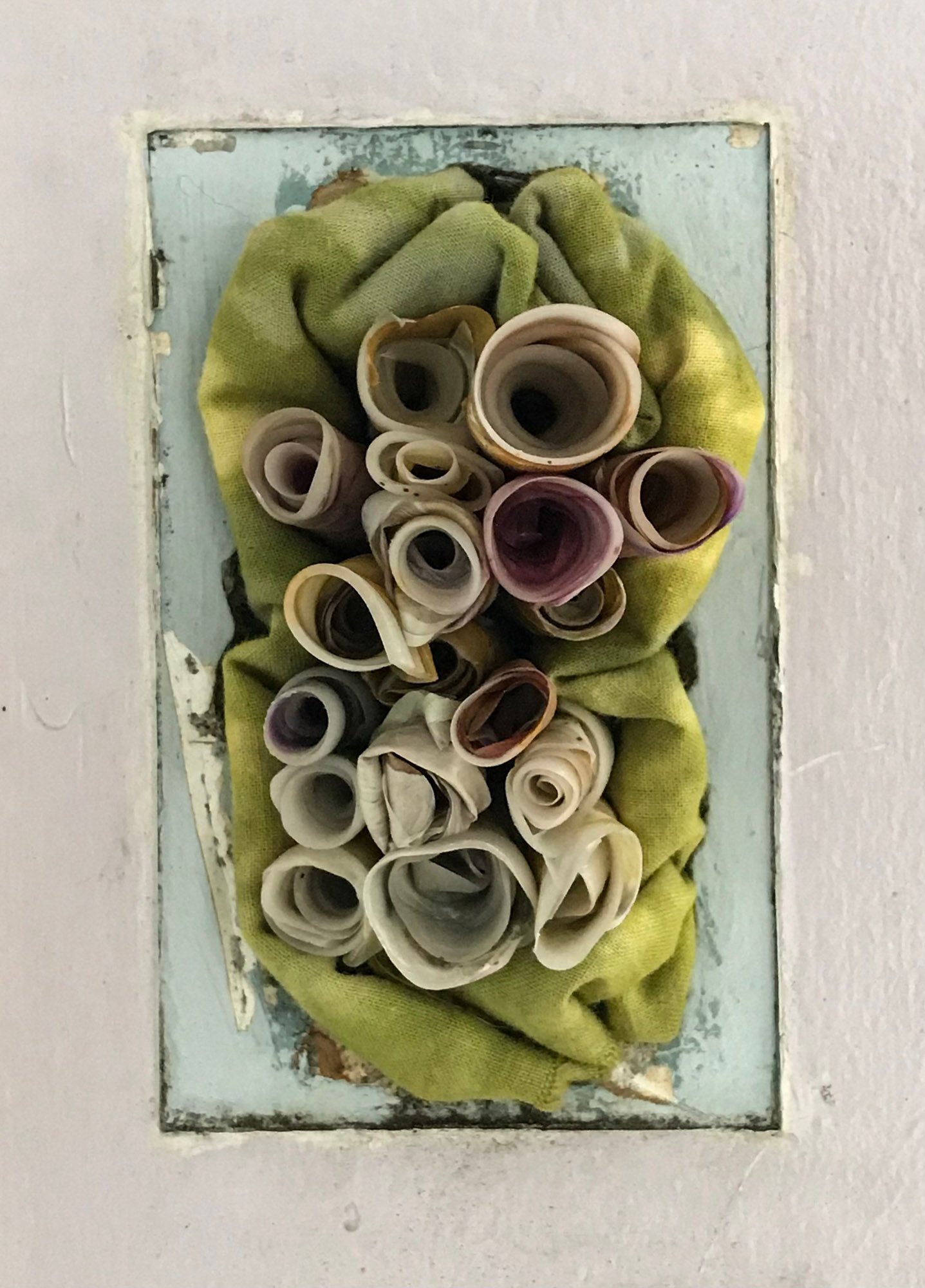

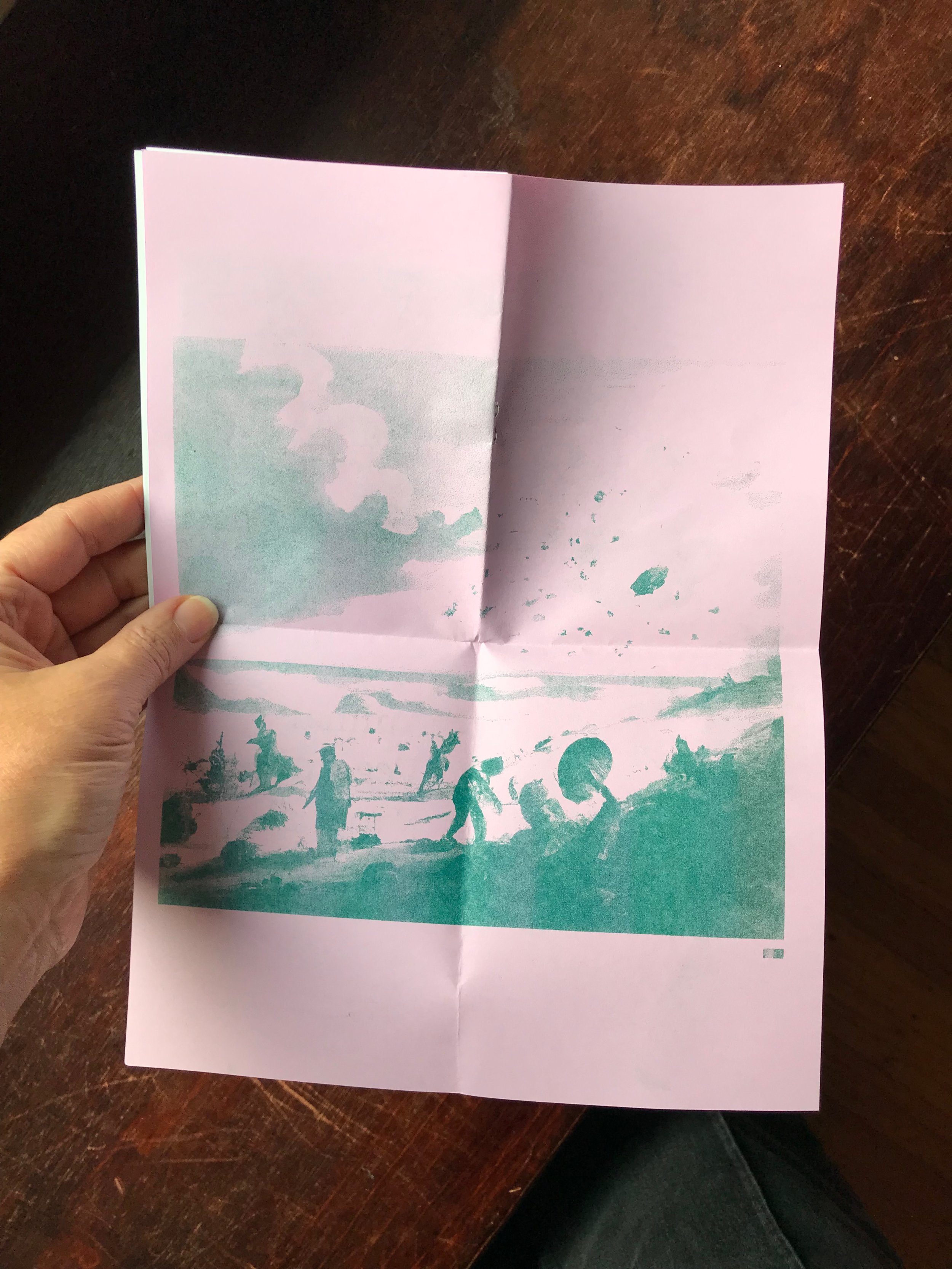

I spent a few days at Saltgrass Printmakers in Salt Lake City, printing monotypes over photographic prints. In a way it would be kind of tidy to think about printmaking as layering akin to the layering of strata in the earth. The reality of strata in the earth is more complicated, though, because—again with the salt tectonics—they don’t behave predictably. Things keep breaking through, seeping out, mingling and shifting. At best that would be a flattering way to describe what was going on with the printmaking process here, since I was getting as experimental as my very generous hosts would let me in mixing inks that might not actually have been intended to go together. Texture! And with so many thoughts converging here, it seemed to fit to get back to collage and printed book pages (this time from one of my father’s geology textbooks). Strategies and ways of thinking are resurfacing that were part of the way I was working when I first started out as an art student. Layers!

This is an ongoing project. A few of the prints and photographs are in a show that’s running for a little while here in Pittsburgh. I prepared this show in collaboration with a group of artists who are mothers like myself, and the long arcs of parenting have been on my mind. My curiosity about geology is a gift from my late father, who waxed surprisingly poetic when he would talk about how the features of the earth got to be that way. As parents we can’t help but cchannel things from our own past into our interactions with our own young ones. It’s hard to know what elements will live into the future—what will be buried, what will dissolve and what will erupt.

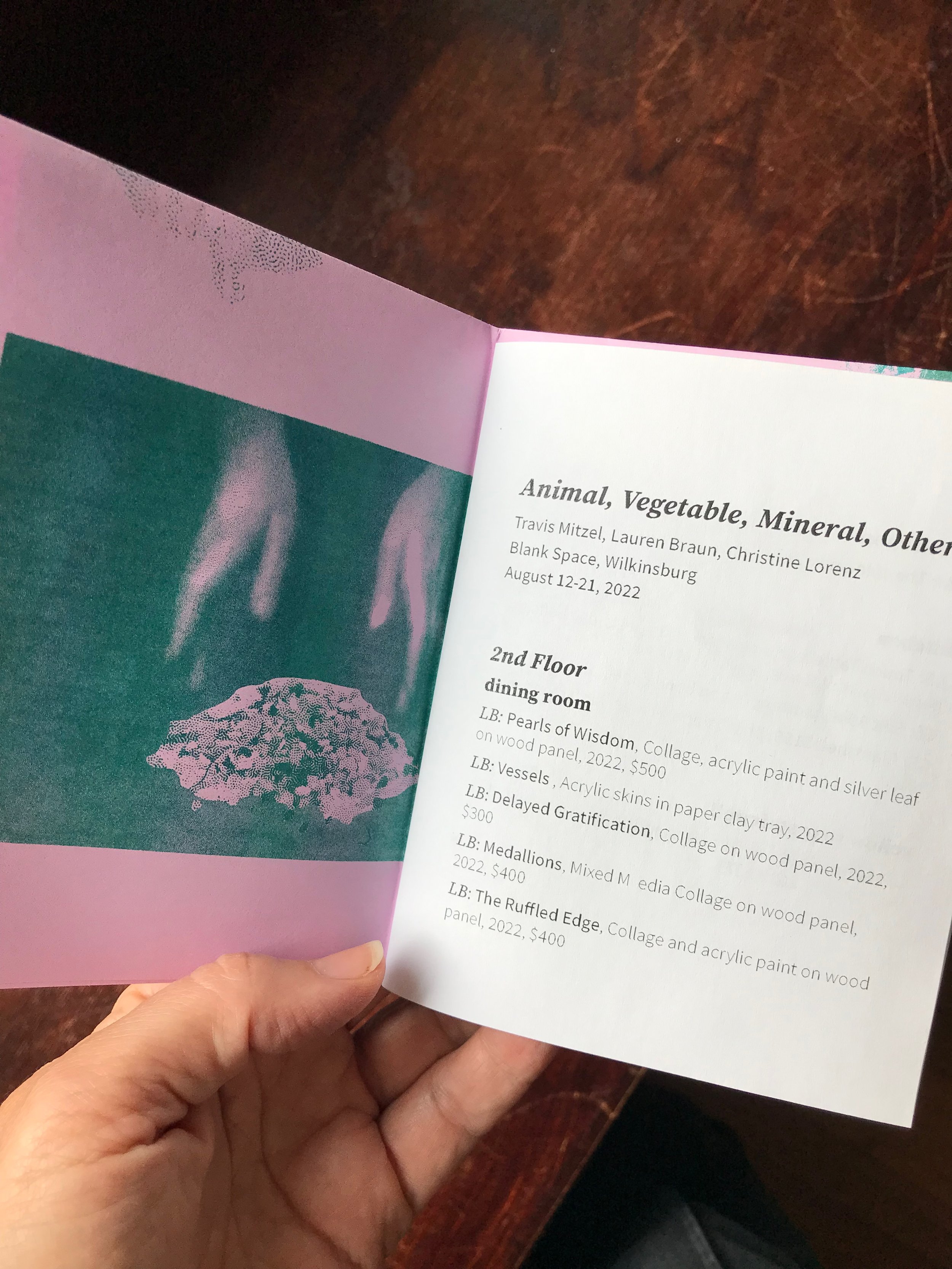

And Also Wide: Artist/Mother Lines opened July 18 at Brew House Arts. This is the new show from Flock Artist Collective, which is what we’re now calling the artist/mother group I started collaborating with at the beginning of 2022. (See more from this group on Instagram at @flock_artists .) There’s an old saying that while life may be short, it is also wide. This show reflects the organic forms of the lines that trace out our lives as artist/mothers—they take on many shapes, they’re always being pulled in multiple directions, and they often converge. The artists in this show bring together a wide variety of materials, strategies, points of view and life experiences, and we build bridges every time we work together.

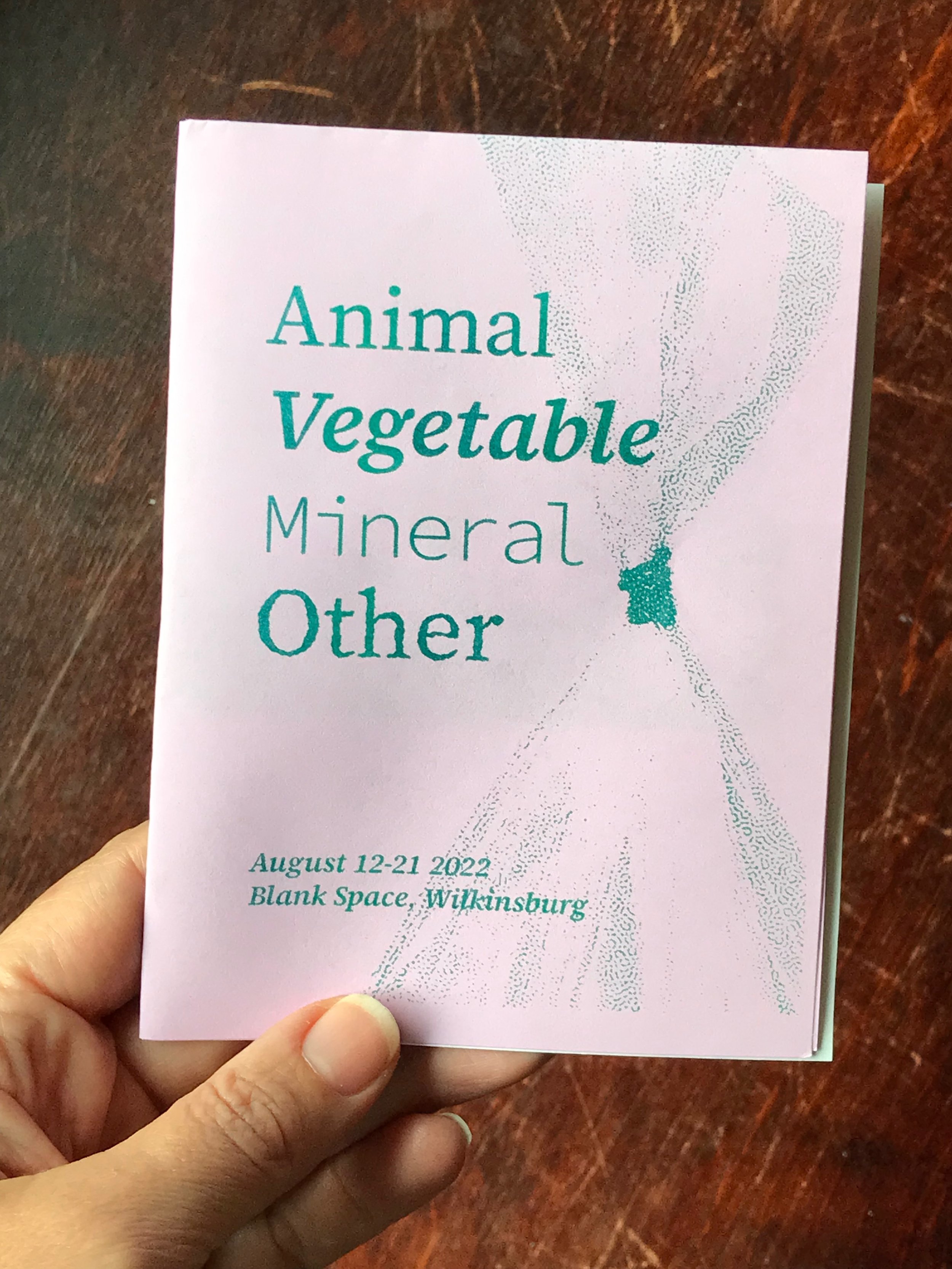

If you’ve read this far, you deserve a treat. Email me at lorenzc(at)comcast.net and tell me you found this offer, and I’ll send you a free copy of the zine I produced for the show, which includes writings from several of the participant artists. They’re doing really meaningful work and it’s a joy to be able to play a role in getting it into the world.

Over time, I keep finding more of my parents in the way I make sense of the world.

When you learn about the layers of the earth, it lets you see the ground you walk on differently. It’s all in constant, endless motion.

My father was an airman, but he never lost his fascination with geology, and he would take any opportunity to tell my brothers and me about it.

Every part of it is shaped the way it is for a reason—because of all the time and changes it has been through.

We are all participating in cycles so much larger than we can grasp.

And you can pick up a piece of it and hold it in your hand.